Somehow, though, that didn't seem to create enough of an argument. I'd be making a whole load of assumptions by focusing on some class and age difference. Instead, I took influence heavily from the Wired.com article on the way in which Chinese view pictures as opposed to Americans and other Westerners. This great difference in views really sparked my interest, but, unfortunately, I was unable to find if there was any sort of difference in evoking ethos, pathos, and logos in Eastern works. I feel that is my piece's greatest downfall, but I intend to continue searching scholarly works to find some regional gap, if it exists.

Between drafts 1 and 2, there was minimal change. I added a paragraph illustrating the picture's history more fully and explaining the world that is Shanghai. I also drew out the appeals to ethos, briefly. Several more hyperlinks and one photograph were added. Other than that, most other changes were gramatical and word-specific.

Going to the Final Draft saw a greater overhaul of the piece. I began by cutting out questionable wording (sort of, etc.) and altering my Statement of Purpose to focus more on the photo than the essay, itself. From there I worked to make paragraphs flow together better, cited more rhetorical appeals, and further explored the regional differences in photography.

Overall, I am quite pleased with the piece, and the help from the Wired.com article and Yang Liu's projects really helped the strength of the piece.

Second Draft

Statement of Purpose

Final Draft

overtook the painted and hand-sketched world, photos have been used to tell stories, explain concepts, and help workers visualize their projects, among a litany of other uses. This is not to say, though, that one shot will have the same meaning for every person or every region of the globe. Cultures that have begun to fully explore this art form each have developed their styles separately, causing different shots to be favored or separate subject matter to draw the viewer's focus. According to a Wired.com article, Eastern and Western peoples may not even see the world they share in quite the same way, just on a physical level.

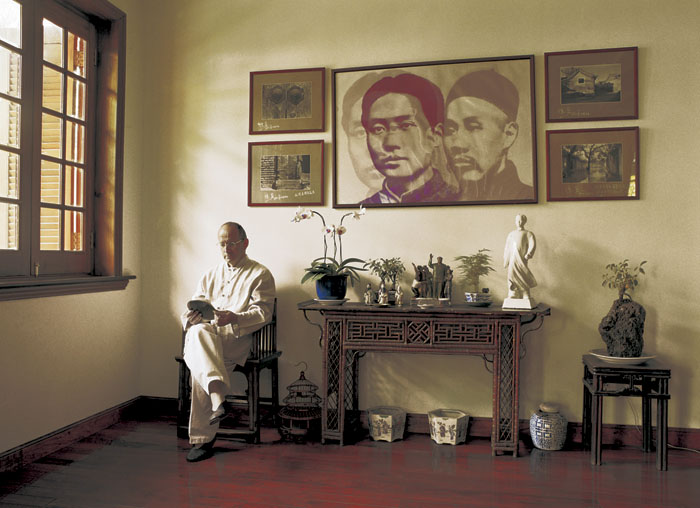

overtook the painted and hand-sketched world, photos have been used to tell stories, explain concepts, and help workers visualize their projects, among a litany of other uses. This is not to say, though, that one shot will have the same meaning for every person or every region of the globe. Cultures that have begun to fully explore this art form each have developed their styles separately, causing different shots to be favored or separate subject matter to draw the viewer's focus. According to a Wired.com article, Eastern and Western peoples may not even see the world they share in quite the same way, just on a physical level.Throughout his vast list of works, Hu Yang uses his art to detail the strange world that is Shanghai. Being a major port city for China, it has long been a hub for the transfer of not only goods, but peoples and ideas, as well. This made the city thrive with a vast and colorful culture, a rare blending of East and West. The artist explains on many of his photographs that this has slowly formed a rift between older and younger generations. The elders worked long hours in manual labor, building the city, mining for resources, and generally putting their blood, sweat, and tears into modernizing Shanghai, and China as a whole. Now that the city is a bustling metropolis, and China often rivals even the United States for economic power, the youth can relax more, and have taken advantage of this sudden economic boon, taking less rigorous jobs, if they even seek employment at all.

This photograph gives the onlooker greater understanding of the many intricate and compelling differences between American and Chinese photography. This is realized by analyzing several pieces of Hu Yang's "Shanghai Longtang Exhibition" for his use of lighting, stylistic focus of people and objects, and his proposed vectors of attention, which evoke each of the rhetorical appeals to ethos, pathos, and logos, then juxtaposing these elements against a Western counterpart's thought of the art of photography. By analyzing the artist's work thus, viewers should come away with a better understanding of world culture and art, as well as to better grasp the degree to which the Western, and primarily American, schools of thought influence the rest of the globe.

This photograph gives the onlooker greater understanding of the many intricate and compelling differences between American and Chinese photography. This is realized by analyzing several pieces of Hu Yang's "Shanghai Longtang Exhibition" for his use of lighting, stylistic focus of people and objects, and his proposed vectors of attention, which evoke each of the rhetorical appeals to ethos, pathos, and logos, then juxtaposing these elements against a Western counterpart's thought of the art of photography. By analyzing the artist's work thus, viewers should come away with a better understanding of world culture and art, as well as to better grasp the degree to which the Western, and primarily American, schools of thought influence the rest of the globe.In his photo, “Shanghai Longtang-Pu Tuo District,” Hu works as he does with any of the other pieces from his Shanghai series; attempting to capture his hometown in its most authentic and unaltered sense. For this reason, the photograph shows relies only

upon the area's natural light. Doing so gives “... Pu Tuo District” a wider appeal, as if this street could be found in any urbanized city. This “natural” feeling reinforces to the audience just how alike this seemingly foreign world can be to a Western onlooker. This street could just as easily be a New York back-alley as a side-street in Shanghai. This familiar feeling helps evoke a sense of ethos, which is what ultimately draws viewers in, making them feel like they could have seen this entire setting before. China may be centuries older than most European nations, with customs and a government unlike any in this hemisphere, but at the end of the day, Chinese cities can be just as ragged as any major Western metropolis, and its people fight many of the same struggles.

upon the area's natural light. Doing so gives “... Pu Tuo District” a wider appeal, as if this street could be found in any urbanized city. This “natural” feeling reinforces to the audience just how alike this seemingly foreign world can be to a Western onlooker. This street could just as easily be a New York back-alley as a side-street in Shanghai. This familiar feeling helps evoke a sense of ethos, which is what ultimately draws viewers in, making them feel like they could have seen this entire setting before. China may be centuries older than most European nations, with customs and a government unlike any in this hemisphere, but at the end of the day, Chinese cities can be just as ragged as any major Western metropolis, and its people fight many of the same struggles.That is not to say, though, that either side's view of the world is symmetrical to the other's. The photograph's layout of figures in space is the most obvious incarnation of the differences in visual appeals between Western and Eastern cultures. Where an American artist may highlight the groups of people and the girl walking alone down the street, Hu begins his visual experience for the viewer at the smoke flume. It's lack of saturation stands in contrast to the dark grays and blacks throughout the rest of the piece. This use of pathos informs the viewer, letting them get in touch with each person the smoke touches. The local onlooker would then follow on to the young girl, to the nearby building, even attempt to gain some knowledge about the people in the background. Here, Hu shows his audience his powerful logos through visual hierarchy. Following this native thought, one clearly notices the photographer's intended purpose: showing how the older generation in the back, used to a life working long hours in smokey coal mines, takes little notice of the thick smoke rising about them, while the youth, a generation who has never known such strenuous work, chokes in the small vapor.

Following Hu in this way makes the viewer take a second look at their own interpretation of the photo and the situation it presents. DesignSwan.com uses the work of Yang Liu to further illustrate many of these seemingly minor differences between the respective cultures (in this case Germany versus China, specifically). Understanding the discongruities between Easterners and Westerners in key places, like the complexities of social groups, the focus on independence, and the importance of oneself, primarily, gives new meaning to the ways in which Chinese photographers work. This picture is working to meld those worlds, because though it is apparent that the girl is one of the main focal points of the piece, she is not the only one. Rather, the photograph works to further explain the inter-connectivity of all of the figures involved, including the inanimate agents.

This being the case, it follows that many intersecting vectors of attention are used in this piece. In attempting to ground the onlooker in the native perspective, one should begin at the outer edge, noting the piece's angle and cropping. Surely when Hu took this picture, there were more workers in the background, and the building on the left took up much more space than it occupies in this representation. But that is not the photo's aim. The way in which the picture is cut leads the viewer to place more focus upon the walking girl, the worker crouched next to her, covered by the smoke, and even the smoke and light, themselves.

As one takes all this in, though, something still feels strange. The artist has

taken the photo at a strange angle, one where the building acts as a structural backbone, making the scene feel more level, yet one cannot help notice the strange angle at which the girl is leaning as she walks. Surely this isn't some natural gimp for her, but instead lends itself to the picture's appeals. Viewers are struck by this seeming oddity, and it makes them focus more upon that which seems unnatural. This speaks to the photograph's appeal to logos, defining how the world within it is arranged, but also defines a rather strict visual hierarchy, leading the onlooker from one object to the next, in an appeal to ethos. Strikingly, though she may not be the most important player within “... Pu Tuo District,” the young girl does lend herself to most of the work's rhetorical elements.

taken the photo at a strange angle, one where the building acts as a structural backbone, making the scene feel more level, yet one cannot help notice the strange angle at which the girl is leaning as she walks. Surely this isn't some natural gimp for her, but instead lends itself to the picture's appeals. Viewers are struck by this seeming oddity, and it makes them focus more upon that which seems unnatural. This speaks to the photograph's appeal to logos, defining how the world within it is arranged, but also defines a rather strict visual hierarchy, leading the onlooker from one object to the next, in an appeal to ethos. Strikingly, though she may not be the most important player within “... Pu Tuo District,” the young girl does lend herself to most of the work's rhetorical elements.Exploring photographs is a great way to learn about someone else. We learned to look at pictures in storybooks at an early age to help us comprehend what was going on. We use large

visuals in newspapers to give an event more clarity to the reader. Even in getting to know a friend or relative, one might sift through old photo albums in an attempt to better connect with another. For this reason, analyzing Hu Yang's “Shanghai Longtang-Pu Tuo District” for its rhetorical appeals, stylized elements, and use of light gives the viewer a better look into not only the day-to-day world of Shanghai, but also the distinct and scintillating anomalies between Western and Chinese approaches to photography, by seeing how a native's project holds to an American's viewpoint.

visuals in newspapers to give an event more clarity to the reader. Even in getting to know a friend or relative, one might sift through old photo albums in an attempt to better connect with another. For this reason, analyzing Hu Yang's “Shanghai Longtang-Pu Tuo District” for its rhetorical appeals, stylized elements, and use of light gives the viewer a better look into not only the day-to-day world of Shanghai, but also the distinct and scintillating anomalies between Western and Chinese approaches to photography, by seeing how a native's project holds to an American's viewpoint.Works Cited